WHO IS CORRECT?

In 2018, the best-performing asset class was cash. We think cash is due some serious attention.

In this Quarter’s Insights, we’ll discuss it as an asset class and as a tool, along with cash management strategies.

Between 2008 and 2016, cash (defined here as the Bloomberg Barclays 1-3 month Treasury index) paid no more than 0.3%. During one of the longest bull-runs in U.S. stock market history, cash became a dead asset. It was talked about in terms like “cash-drag” and “cash-is-trash.” After the last two years of rate hikes, the short end of the yield curve is finally starting to look more attractive.

CASH AS AN ASSET CLASS: EVERYTHING YOU EVER WANTED TO KNOW ABOUT THE YIELD CURVE, BUT WERE AFRAID TO ASK

The yield curve is a line graph that plots the current yield of fixed income investments across different maturities, from shortest maturities (1-month) to the longest (most often 30-year, but sometimes longer). While the U.S. Treasury yield curve is most commonly discussed, this concept exists across all types of fixed income assets, including municipal bonds and corporate bonds as well as geographies.

Often, a country’s sovereign bond yields become the baseline for nearly every other investment as they’re considered to be predominantly risk-free. If an investor can buy a risk-free government bond that’s paying 4%, why would they buy a corporate bond that’s only paying 3.5% and take on the additional risk of default? U.S. corporations typically pay more than U.S. Treasuries to entice investors to lend them money given the additional risks.

The short end of the curve impacts short-term investments like CDs and your bank’s savings account yields. The middle and long ends of the curve help set rates at which corporations can borrow on their own 10-year bonds, and what you pay on your mortgage. Given that longer time frames allow for potentially more instances of risk (interest rate changes, economic changes, changes in inflation, etc.) you would expect that investors would require a higher yield the further out in time they lend, as they’re exposing themselves to these risks.

In 2002, for example, the 3-month U.S. Treasury bill yield was about 1.7%, the 3-year U.S. Treasury Note yielded about 3.75%, and the 30-year U.S. Treasury bond yielded about 5.5%. An investor could expect to earn, roughly, an additional 4% per year by purchasing long-term bonds over short-term bonds.

Currently, the yield curve is “flat”: It doesn’t have much curve to it. In the first quarter of 2019, the 3-month yield was about 2.4%, with the 3-year at about 2.

5% and the 30-year at about 3%. Investors right now are only expected to earn an additional 0.6% per year by purchasing long- term bonds over short-term bonds. Does it make sense to expose yourself to the risk of inflation, the economy, interest rates, and you-name-it for an additional 0.6% per year over the next 30 years? We didn’t think so either.

CASH AS A TOOL

It has long been said that wealth builds given “your time in the market, not timing the market.” That doesn’t mean that when things go south, a little bit of risk management is a bad idea. Even when cash is paying “nothing,” it still has value as an option, and optionality (dry powder) has value.

That’s why we implement our Moving Daily Average (MDA) strategy on both U.S. and international stocks. Parking assets in cash while markets are declining gives us the opportunity to buy back into those markets at lower prices. We’ve discussed this in previous Insights. With cash and cash proxies now paying decent yields (more on this further on), trades like the MDA become much more effective. For more information on our MDA approach, please revisit our Fall 2017 Tactical Allocation and The Daily Moving Average.

Another useful attribute of cash that should not go overlooked is its value as a safety blanket. When the going gets tough, cash doesn’t do anything. Cash doesn’t rally either, but cash doesn’t crash. When nearly everything in a portfolio is down (like 2018) there’s a huge psychological benefit to be able to point to something that’s not in the red.

CASH MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

Many clients pull cash from their portfolios, either on a regular basis, or from time to time for one reason or another. By no means, however, should an investment portfolio be used as a checking account. Not only would transaction fees add up, but there’s a statistical phenomenon sometimes referred to as reverse dollar-cost averaging that may also negatively impact results.

We advise clients not to take distributions from their investment portfolios any more frequently than monthly. So if you shouldn’t use your investment portfolio as a checking account, how much cash should you keep on hand?

This is the $64,000 question! How much is a very detailed answer that should be tailored to you. This resource is often called an “emergency fund,” but it doesn’t necessarily need to be for emergencies. A prudent practice standard suggests a minimum of three-to-six months’ worth of expenses.

And there are a multitude of variables beyond “emergencies” that you should take into consideration to adjust your cash on hand.

What’s your income relative to your expenses? How is your job stability? Is your company in a layoff mode? Are you a salesperson with fluctuating earnings? Do you have a major purchase/ expense coming up? How is your health? How many people (or pets!) depend on you? Simply put, the more short term in nature your needs, and the more volatile your resources designed to meet those needs, the more cash you should have available. So you can count on cash being there when you need it.

Of course, your situation is unique. We recommend engaging your Wealth Advisor and/or Regional Director to consider your specific needs for cash reserves.

This brings us to another very important consideration: How much is that cash earning?

If you’re keeping excess cash in your checking or savings account at your local bank, you’re not likely earning much on it. Currently, the average yield on a bank savings account is 0.09%. With such a low yield, we would recommend that you hold less cash.

But what if you could earn 2% or more?

Then cash would play more of a meaningful role in a financial plan, even for those who don’t otherwise need to hold much of it.

Over the course of a year, even as little as $5,000 in a savings account earning 2% could earn enough to pay for a nice dinner and a bottle of Barolo. For those who prefer to hold quite a bit more cash, the earnings could be more significant.

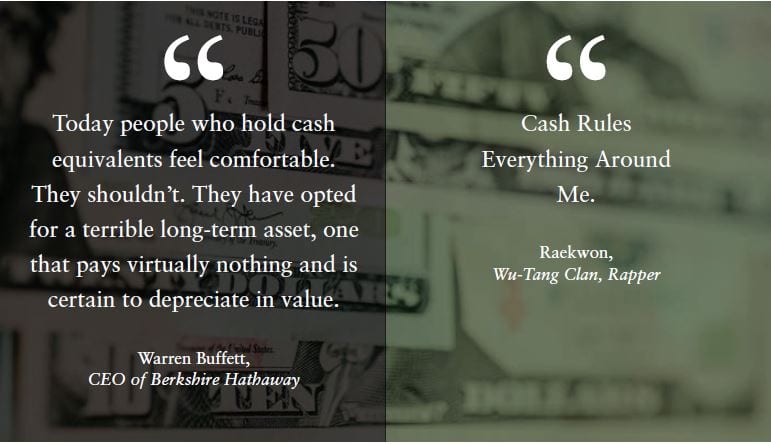

If you’re interested in learning more about cash management strategies with Halbert Hargrove, we suggest talking to your Regional Director or Wealth Advisor. The fact is, both Warren Buffet and Raekwon have a point. Cash is not an outstanding long-term investment, but it can be a tool that can be used both within a portfolio and outside it to facilitate better results for investors.

For more information or questions, please contact Halbert Hargrove at hhteam@halberthargrove.com.

RISKS AND DISCLOSURES

The views contained herein are not to be taken as an advice or recommendation to buy or sell any investment. Any forecasts, figures, opinions or investment techniques and strategies set out are for information purposes only, based on certain assumptions and current market conditions and are subject to change without previous notice.

All information presented herein is considered to be accurate at the time of writing, but no warranty of accuracy is given and no liability in respect of any error or omission is accepted.

This material should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any securities or products mentioned herein. In addition, the Investor should make an independent assessment of the legal, regulatory, tax, credit, and accounting and determine, together with their own professional advisers if any of the investments mentioned herein are suitable to their personal goals. Investors should ensure that they obtain all available relevant information before making any investment.

It should be noted that the value of investments and the income from them may fluctuate in accordance with market conditions and taxation agreements and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Both past performance and yield may not be a reliable guide to future performance.

The information presented herein is for the strict use of the recipient who have requested such information and it is not for dissemination to any other third parties without the explicit consent of Halbert Hargrove.